Description

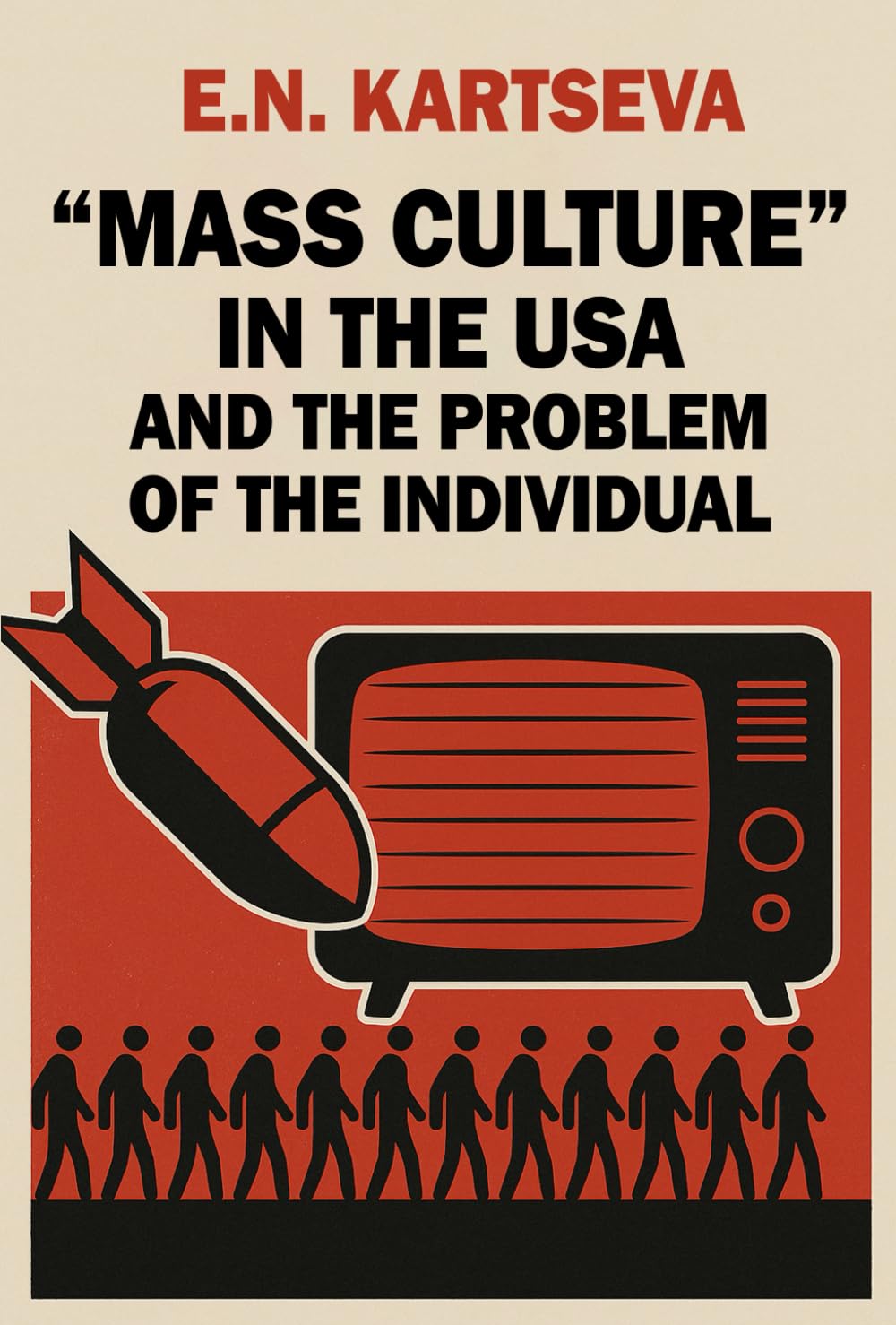

“Mass Culture” in the USA and the Problem of the Individual is a dissection of the major means of America’s cultural apparatus. Written by Soviet critic E.N. Kartseva and first published in Moscow in 1974, this work exposes “mass culture” not as the flowering of democracy or progress, but as the ideological arsenal of a Western bourgeoisie in decline.

Kartseva begins with two aphorisms: the humanist’s faith that “the pen is mightier than the sword,” and the cynical claim of modern sociologists that “mass media are more powerful than the atomic bomb.” From this contrast unfolds the book’s central question: does mass media liberate the individual, or does it enslave him in illusions? Is the modern American a fortunate participant in a global conversation, or a prisoner of the television screen and the advertising slogan, trapped in a cage without locks?

Through detailed engagement with and criticism of Western thinkers such as Fromm, Riesman, Marcuse and McLuhan, Kartseva demonstrates how the crisis of individuality in capitalist society created fertile ground for a culture of manipulation. The press levels truth and trivia alike; commercial film reduces art to stereotype and spectacle; advertising hypnotizes the consumer with illusions of happiness; political campaigning becomes indistinguishable from Hollywood. In this culture, heroes give way to celebrities, art to kitsch, individuality to conformity. Even apparent optimism masks a deep, unconscious despair — the ideology of a ruling class aware of its own decline.

Contrasted to this hollow “mass culture” is the conception of the new culture: democratic, humanistic, genuinely for the people, never pandering to backwardness but always raising the masses to higher spiritual levels. The difference is not quantitative but qualitative: between “reproducible” culture manufactured for consumption and “live” culture born from human creativity and struggle.

Kartseva’s analysis remains relevant. She demonstrates how “mass culture” functions as both myth and surrogate religion — offering not reality but a system of illusions, distracting the public from contradictions in capitalist life. It is a culture that pacifies rather than enlightens, creating a pseudo-world where cars, clothes and television replace meaning, and where advertising-style thinking substitutes for true aesthetic perception.

This book is both an academic study and a polemical intervention in the ideological struggle of the 20th century — reprinted for our own age of digital distraction and mass manipulation, when this mask for prevailing social relations has only strengthen its grip on the people and extended across the entire globe.